Quartz, Palms, and Hidden Waterfalls: A Hike into Oswit Canyon

- Feb 24, 2025

- 9 min read

Why Hike Into Oswit Canyon

Oswit Canyon doesn't announce itself in typical bold Palm Springs fashion. There are no big trail sign or information kiosks. It's not a 'secret or off-the-grid' hike but it does not draw as much attention as other well know hiking trails in the valley. It simply begins in a wide sandy wash tucked between rugged foothills on the southern edge of the city. Oswit isn't the largest canyon in the Coachella Valley but what makes it special is its ecologically diversity — cacti, wildflowers, and desert fan palms all within a 2 mile hike from the trailhead; add a waterfall and incredible geology and you've got the makings of a great short hike.

Hike Distance: 4 miles

Elevation Gain: 974 feet

TrailsNH Hiking Difficulty Calculator: 88 – Moderate.

Special Note: However based on the rock scrambling and trail finding issues, you may want to consider this hike more difficult than the rating implies.

Click here to navigate to the TrailsNH website for a description of the hiking difficulty calculator.

Let's Start Hiking in the Green Desert

The hike and the views begin where the pavement stops. On this chilly morning, clouds from the previous day's storm were clinging to the mountains peaks along with some fresh snow.

The sandy wash at the trailhead is part of a much larger alluvial fan that spills out of the San Jacinto Mountains. The fan was built during thousands of flash floods. One storm at a time as the mountains empty themselves into the valley, stacking rocks in chaotic layers and depositing sediments.

Mountain Effect - Water Flows Downhill

The one word I would use to describe the wash was 'green'. Desert washes collect and nourish more plant life than other sections of the desert for a number of reasons.

When storms systems from the Pacific Ocean are forced to rise over the 10,000+ foot San Jacinto Mountains, the air masses cool and condense, resulting in heavy rain fall on the other side of the mountains. Any moisture which spills over the mountains, falls in the Palm Springs foothills. So although the Coachella Valley is a rain shadow desert, Palm Springs receives higher annual rainfall than other desert communities further East.

Steep canyons like Oswit funnel storm runoff into narrow channels,. Even modest rainfall at higher elevations becomes a concentrated flow at the canyon mouth. Runoff brings not only needed rain but also nutrient-rich sediment as it scours the canyon.

Nothing but green.

Flashfloods - Build Sandy Sponges

Sediments washed down from the mountains for tens and hundreds of thousands of years bring loose nutrient-rich sediment that stores moisture below the surface, safe from the sun. In addition, the mountain runoff also carries seeds and disperse them along the entire length of the wash. After summer monsoonal rains and winter storms, many cacti, shrubs and wildflowers seized the ideal moment to bloom with vibrant colors.

Standing tall, a crown of bright yellow flowers on the California barrel cactus are easy to spot.

The bloom on this beavertail cactus were almost swallowed up by the invasive grasses.

Not all the cacti were flowering; this gander cholla is still several months from displaying its yellow-green blossoms. Gander cholla have a limited distribution, found solely in Southwestern California.

This Engelmann’s hedgehog or Strawberry cactus is also several months away from flowering. It produces large 2 to 3 inch wide tubular flowers that range in color from bright magenta to pale pink, but only last for 5 days opening in the morning and closing at night.

Wild canterbury bells were hiding among the rock. These clusters of purple bell-shaped flowers look almost ornamental against the rocks.

Desert chicory

Distant phacelia form soft, lavender-blue flower cluster.

Fiddleneck are named for their tightly coiled flowers spikes that resemble the neck of a fiddle,

The tiny white blooms of annual cryptanthas can be easily overlooked. Much like fiddleneck and distant phacelia, annual cryptanthas is covered in tiny white hairs known as trichomes, which coat the leaves, stems, and flowers. Trichomes serve many function including:

Reduce water loss by insulating the surface and slowing evaporation.

Reflect sunlight, keep temperatures lower and prevent heat stress.

Protect against sand abrasion, reducing physical damage to delicate tissues.

Shield against wind drying effects.

This adaptation protects these brilliant blooms in a challenging landscape.

The chuparosa, also known as the hummingbird bush, is a vibrant desert shrub native. It thrives in arid environments and blooms primarily in spring, producing tubular red or orange flowers that attract hummingbirds—hence its name, which means “sucks rose” in Spanish. The plant typically grows up to five feet tall and has succulent-like stems with few or no leaves during dry seasons. Chuparosa is valued not only for its drought resistance and wildlife appeal but also for its role in native landscaping and habitat restoration in desert regions.

In less than a mile, we left the Oswit Land Trust property and entered the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument. At the conclusion of the blog, I'll share information on the role the Trust played in protecting this canyon from development.

Around the 1-mile mark, the canyon is characterized less by plant life and more by rock formations.

Building Boulder Fields

Moving deeper into the canyon, the walls grow taller and we're hiking through a canyon that is literally falling apart.

At this point, the trail disappears. The task is now to find the easiest route through the rockfall zone.

Initially, the path was relatively straightforward, requiring just a simple step over or around.

Then we came face-to-face with a rockfall debris field, a common occurrence here.

Rockfalls in Oswit are the result of a powerful partnership between faulting and weathering. The canyon walls sit within the San Jacinto Fault Zone where tectonic movement has fractured the bedrock into blocks and slabs; leaving giant blocks loosely attached to the steep canyon walls. Look above my head to see the evidence of this weathering. How long will it be before this section breaks apart and falls onto the canyon floor?

With the fault creating the initial joints or cracks, then weathering takes over and expands every weak point. Desert temperatures swings cause the rocks to expand by day and contract at night, slowly widening fractures. Winter storms drive water deep into joints, and when it freezes, the ice expands like a wedge, prying the rock apart. The result is the already fractured cliff walls weaken even more until gravity takes over and pulls the blocks free. Some rockfalls are small - single boulders bouncing into the wash; Others are large slab failures that send tons of granite crashing down the canyon floor.

The chaotic landscape of massive granite blocks, fractures slabs and angular debris, you see in Oswit Canyon is a snapshot of a landscape in motion. The canyon is actively widening, slopes are retreating, and the canyon floor is littered with more boulders.

Rockfalls are largely due to the steepness of the canyon walls and aren't a sign of an unusual danger — they are part of a natural process.

Faults create the cracks

Weathering widens the cracks

Gravity releases the blocks

This process has been repeated countless times over the thousands and hundreds of thousands of years in the canyons. Each rockfall removes a little more material from the cliffs, causing them to retreat over time.

The canyon walls we see today are not the same walls hikers will see 50 years from now.

Sometimes, crawling under the rock piles is easier than climbing over them.

Ancient Plumbing

Of all the incredible sights in the canyon, one of the most impressive were these quartz veins slicing through the bedrock. Dave is standing on a large dark banded metamorphic rock streaked with white lightning-like quartz veins.

Step 1: The rock was fractured by movement along the San Jacinto Fault Zone,

Step 2: Hot fluids (400-800°F) rich in silica under great pressure are forced into the cracks.

Step 3: Quartz crystals precipitate out as fluids cool, cementing the fractures with white veins.

Step 4 Uplift and erosion stripped away the overlying rock leaving the veins exposed.

Quartz veins don't form on the surface, they begin 1-6 miles beneath the Earth's surface. Iron oxides in the superheated fluids left rusty-red stains in places. These basement rocks are probably hundreds of millions of years old. Dave is literally walking on ancient remnants of a plumbing system from the Earth's crust.

Faint Sounds of Water

The same San Jacinto Fault Zone that uplifted these mountains have created a zone of crushed and pulverized rocks. High above the canyon, rainfall and snowmelt seep deep into fractured bedrock in the San Jacinto Mountains. This water slowly travels downslope through a network of cracks and faults until it meets less-permeable rock. With nowhere else to go, it’s forced sideways, emerging as steady groundwater seeps that lie just beneath the surface and at times on the canyon floor.

The presence of these California fan palms is a clear indicator of these seeps. Palms can only survive where they have year-round uninterrupted access to groundwater. In order to survive, their roots must be able to tap directly into these seeps.

A short distance away, there were several large pools with water spilling over the rock slabs.

The bright green growth in the standing pools of Oswit Canyon is aquatic algae. These algae grow as soft, mat-like sheets or stringy filaments attached to submerged rocks. In clear water, they almost look like underwater lawns. It look extra vibrant because as groundwater seeps upward through the fractured bedrock, it picks up calcium, magnesium and other trace nutrients that act as fertilizers for the algae.

The sound of water flowing over the canyon walls break the silence in the canyon. It’s not loud but during early spring we could hear water splashing in the pool at the base of the canyon wall. Don't expect a dramatic cliff-drop scene, it's more of a small cascade over hanging bedrock. But it’s amazing to see and hear nonetheless.

The waterfall is born in these mountains and fed by:

Summer monsoons and winter storms that surge down the steep granite slopes.

Snowmelt from higher peaks in the springtime.

Seeps and springs.

So during and shortly after rainfall, or during snowmelt events from higher elevations of the San Jacinto Mountains, the waterfall feeds a pulse of surface water to the canyon. But this contribution is short-lived.

The waterfall’s flow is mostly tied to precipitation, so once runoff drops, the waterfall becomes little more than a trickle. Nothing like the sound of cascading water in the desert.

It’s easy to assume that the surface pools and lush greenery in the upper canyon are nourished by this small seasonal waterfall. However, the life-sustaining water originates from the reliable seeps along the canyon floor. These gentle seeps continue to provide water long after the waterfall has dried up, allowing the native fan palms to flourish in this area.

Several California fan palms grow at the base of the waterfall. Their healthy condition indicates a stable groundwater supply, since they wouldn't survive if they depended solely on a seasonal waterfall to meet their needs.

Time for a selfie, snack and a return to the trailhead.

As we leave the waterfall, undeniably the highlight of the hike, it's important to remember that this remarkable landscape is not maintained by the stunning waterfall but by the gradual, steady flow of water through the rock.

A short break on a big rock and ...

... one last trip through the rockfall zone.

Oswit Canyon was another excellent hike in the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument. We'll definitely add it to the list of hikes that we offer to friends and family when they visit.

As we approached the trailhead, the clouds which had followed us most of the day were looking more ominous.

Here is a satellite view of the trail we followed.

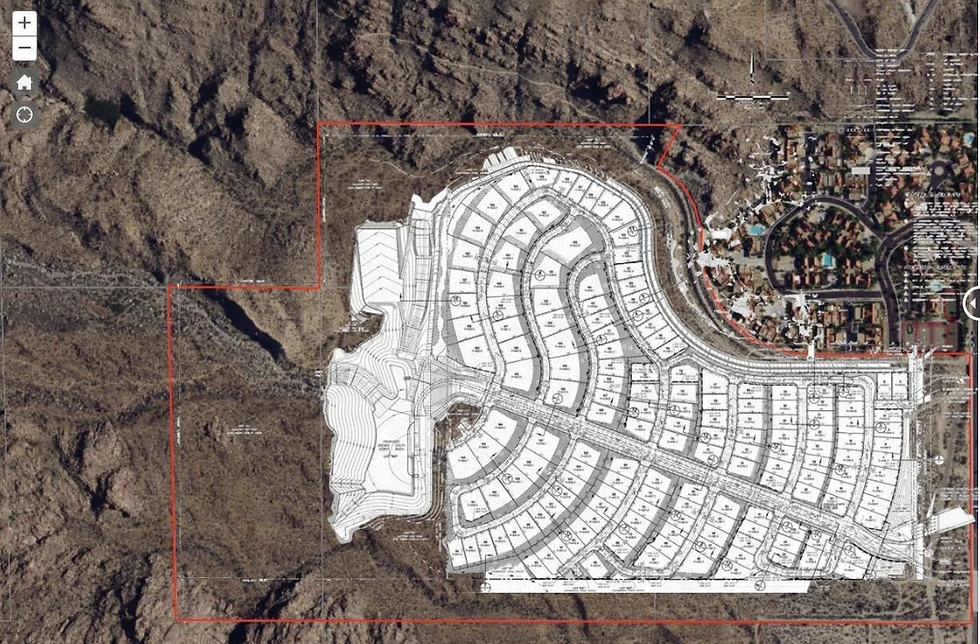

Saving the Canyon

In 2016, local hikers and residents learned that Oswit Canyon a wild, unprotected alluvial fan at the base of the San Jacinto Mountains was slated for a large residential development. That plan called for hundreds of homes and flood-retention infrastructure that would have destroyed habitat for desert wildlife and erased one of the last natural canyons near Palm Springs. Below is an aerial photo of the proposed development plan.

In response, a grassroots group formed Save Oswit Canyon, rallying community support. Over a period of nearly five years, the group gathered more than 5,000 petition signatures, organized city-level advocacy, raised funds through public donations, and secured grants from state and federal conservation programs. In October 2020, Save Oswit Canyon closed escrow on 114 acres for approximately US$ 7.15 million, permanently protecting the canyon from development. The land was then placed under the stewardship of Oswit Land Trust — ensuring public access and protection of native habitat for endangered species, migratory birds and desert wildlife, as well as preserving unique desert geology and canyon ecology for future generations. This victory stands as a powerful example of how community mobilization, legal advocacy, and conservation funding can combine to save fragile wild landscapes. Below is an aerial photo of how the canyon will look in perpetuity.

Thanks to the Oswit Land Trust for fighting the good fight!

240223

Comments