Where the Earth's Crust Crumbles: Hiking Skeleton Canyon in the Mecca Hills

- Steve

- Nov 7, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Dec 25, 2025

Why Hike Skeleton Canyon

I remember the first time I saw these red hills when we were driving on Painted Canyon Road in the Mecca Hills. I had never seen anything like this and wanted to find out more.

After some research, I found an online topo map that labeled the area as Skeleton Canyon. The fact there was almost no online information about hiking Skeleton Canyon only increased my interest in exploring the area.

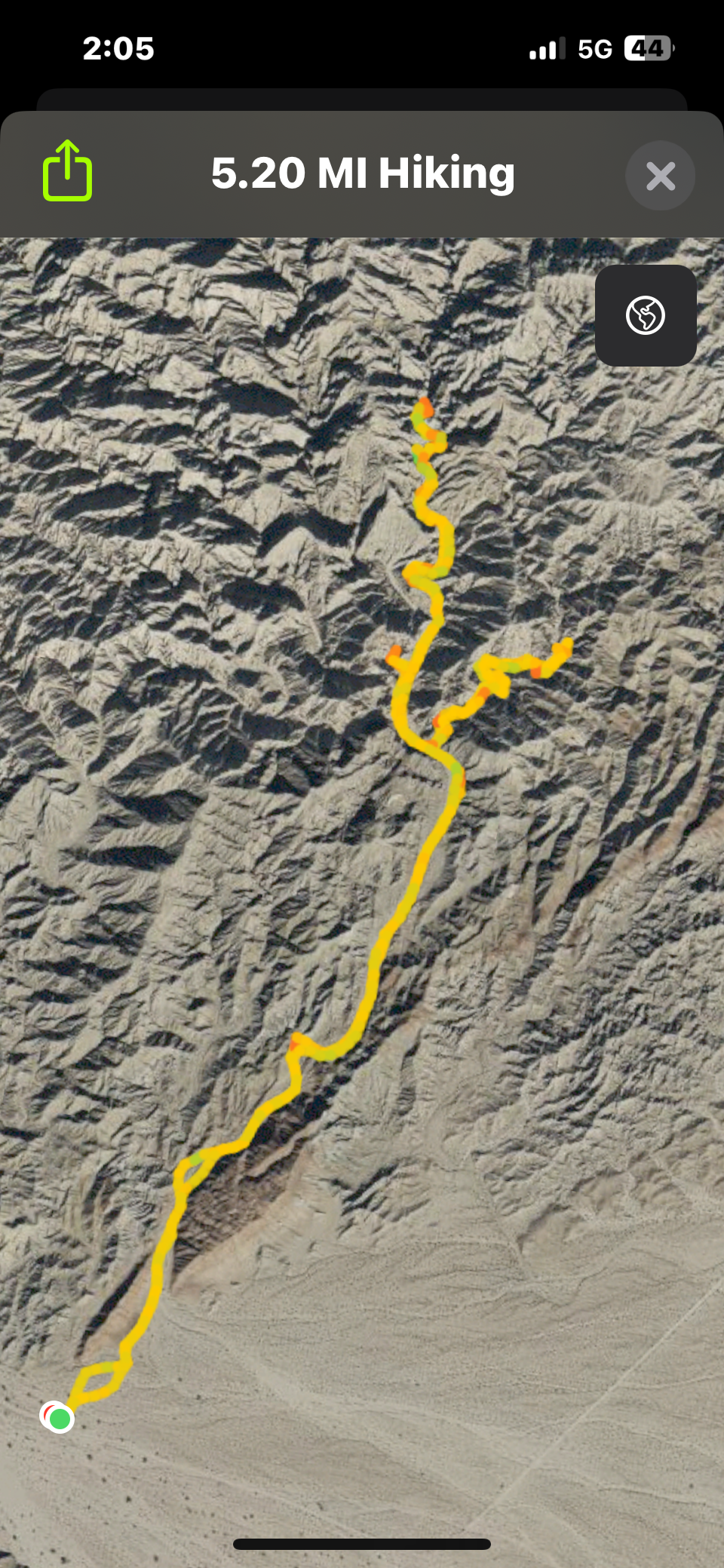

Hike Distance: 5.2 miles

Elevation Gain: 568 feet

Prominence: 2,150 feet

TrailsNH Hiking Difficulty Calculator: 77 – Moderate

Click here to navigate to the TrailsNH website for a description of the hiking difficulty calculator

Let's Start Hiking the Wrong Canyon

During our initial attempt to hike the canyon, we were somewhat confused and ended up exploring a smaller canyon situated just northeast of the 'real' Skeleton Canyon.

We realized our mistake, retraced our steps (blue line), and entered the actual Skeleton Canyon.

Let's Start Hiking Skeleton Canyon

Let's start over. We parked the car at a ‘pullout’ on Painted Canyon Road and began hiking across a sandy wash that leads to Skeleton Canyon.

The red hills located just before the canyon entrance show signs of heavy ATV traffic which unfortunately is legal since the hills are not within the designated Mecca Wilderness area or Chuckwalla National Monument.

Following the Water

Usually washes in the Mecca Hills have a soft sand consistency but at the entrance to Skeleton Canyon it’s a hard packed surface that’s easy to walk on. The firmness underfoot comes from a combination of geology, hydrology, and wind, all working together. The canyon and side drainages funnel stormwater into the wash. When those rare desert downpours happen, water rushes through the entrance with enough force to compress loose sand and flush out the softest, loosest sediments. Weathering breaks down some of the rocks comprising the hill into fine clay and silt which mix with the sand in the wash. When those fine grains get wet and then dry in the sun, they create a weak natural cement. During dry periods the wind strips away any remaining loose grains leaving behind a surface that dries into a hard, flat surface called desert pavement. For the majority of this hike, we’re lucky to have this surface to walk on.

This wash supports a thriving plant community not only in the winter and spring but also in the fall after monsoonal rains feed plants that have been cooked by summer temperatures.

After a flood scrubs the wash, before annuals germinate and trees send out more leaves, the cheesebush is already turning green. This desert expert has dormant buds and carbohydrates stored within its roots that allow it to leaf out almost overnight after a rain event. Although cheesebush green up fast, it can also shut it down quickly. It rapidly drops its leaves when drought returns ensuring it will survive the desert's boom or bust rain cycle.

Cheesebush produce small pale yellow to greenish flower clusters that aren't as showy as wildflowers but are important to the desert ecosystem. The flowers provide early season nectar and pollen for bees and other insects as they emerge from winter dormancy. The seeds they produce also provide food for insects and small mammals.

Another master of desert adaptation that also greens up quickly after a rain event is the saltbush. These shrubs tolerate high concentrations of salts in the soil by excreting the salts through specialized leaf tissues and surface bladders that prevent the toxic ion buildup in cells that perform critical functions. The ability to excrete salts through its leaf structure is a function shared with several other plants in the desert wash habitat.

Entering the Canyon: First Impressions of a Broken World

Entering the canyon, the first thing that stands out are the low, brick-red to maroon colored hills. So what are these hills and why do they appear in this canyon and only a few other select areas in the entire Mecca Hills complex?

The story begins with an understanding of where we stand.

The Mecca Hills complex sits atop numerous faults within the San Andreas Fault Network but in Skeleton Canyon we are standing directly on the San Andreas. According to the California Department of Conservation's interactive fault activity map, the canyon entrance (marker circled in blue) is located on the San Andreas Fault and adjacent to Skeleton Canyon Fault and Painted Canyon Faults.

In an active fault zone like Skeleton Canyon, rocks get shattered and crushed as the North American Plate, which we are standing on, grinds against the Pacific Plate. This area is referred to as 'damage zone' and it can be tens to thousands of meters wide.

However, the narrow strip where the plates actually grind past each other is referred to as the 'fault core zone' or 'fault plane' and it is estimated to be 100-300 meters wide at the surface in the canyon. Within the fault core zone, rocks aren’t crushed, they’re destroyed. Individual rock grains are milled into a soft almost clay-like powder the equivalent of rock flour. This powdery substance is called 'fault gouge'.

In this canyon, fault gouge originates from iron-rich rock so the powder is oxidized or rusts when it comes in contact with oxygen and groundwater deep within in the core. This entire region of the red hills is made of fault gouge, the powdered remains of rocks caught within the grinding teeth of the San Andreas Fault.

Water Shapes the Fault Gouge Hills

The hills don’t rise sharply or display bold layers and knife-like ridge lines. Instead they tend to be rounded because gouge is extremely weak, fine-grained, and easily eroded. Rain knocks it down, runoff smooths it, and every monsoon season the slopes quietly slump and settle a little more. Over time, the landscape relaxes into rounded hills.

Geologists cannot assign a precise age to the red gouge because each shift in the fault, crushes new rocks and combines fresh gouge with older gouge. By the time gouge reaches the surface, it has been blended, reworked and chemically transformed so many times that its 'original date' has been lost forever. The most we can say is the fault gouge is as old as the fault movement that pulverized it and the San Andreas in this segment is younger than 2-3 million years. Based on uplift along the faults, this fault gouge is probably tens to hundreds of thousands of years old.

A close-up view of the fault gouge reveals how easily it weathers and erodes.

Why the Fault Gouge Hills Vanish and Reappear

As you walk down canyon, the red fault gouge hills rise beside you reaching heights of tens to hundred of feet.

The suddenly the hills fade away and are replaced by more firm multi-colored rock formation with occasional streaks of red.

A little farther down canyon, the red hills return. The reason for this is simple; the fault core zone doesn't run through the canyon in a straight line. It bends, splits and sometimes steps to one side or the other of the canyon. Where the canyon slices directly across the fault core zone, gouge spills out. But where the canyon drifts away from the fault core zone or where stronger rock covers the gouge, the red hills disappear.

Desert Plants in a World of Flashfloods and Broken Rocks

Despite the canyon's tortured geology, a surprising number of desert species have adapted to living in this fractured and mineral-rich environment.

After wet winters, the wash bursts with annual wildflowers. A good display in a place as stark and isolated as Skeleton Canyon comes down to flashflood geology and soil chemistry. First the wash acts as a seed bank. Every flood drops fresh sediment and buries thousands of dormant seeds. These seeds belong mostly to annuals that have adapted to long drought cycles. They lie in wait through scorching summers, protected by the loose sandy cover, and germinate only under the right conditions like these desert sunflowers

Secondly, the mix of crushed rock, clay-rich gouge and mineral laden sediment create pockets that hold moisture a little longer than the open desert. Early winter rains (November-January) trigger these cool-season germinators. Their seeds are programmed to sprout when soil temperatures are low enough, moisture arrives long enough to soak in, and the days are short enough to signal that winter is here. This ghost flower got the right message.

Notch-leaf scorpion weed

Heartleaf suncup

Sand blazing star

However, not all wildflowers germinate in winter. Some wildflowers like this trailing windmills are monsoonal wildflowers that typically bloom after summer rains.

Although these Emory’s rock daisies can bloom until late November, they are not monsoonal wildflowers. In general, fall annuals in the Mecca Hills are usually smaller because they grow under hotter, drier, and more time-limited conditions. Their life strategy is about speed. Whereas winter annuals get cooler weather and deeper moisture, so they tend to be taller, fuller, and more conspicuous in bloom.

Walking through the wide wash, it’s hard to miss two of the desert’s toughest specialists: desert holly and honeysweet (Tidestromia suffruticosa). These shrubs are perfectly engineered to survive in this punishing environment.

Desert holly is the classic drought warrior and salt tolerance is one of its critical survival adaptation. Most plants can not handle the high salt content in these soils, but desert holly actually uses it. Holly pulls salts from the soil and concentrates them in its leaves. By excreting salts it prevents their harmful build up which would interfere with critical cells functions. The salt coating also helps deflect sunlight, keeping leaf temperatures lower. Desert holly doesn’t just tolerate harsh soil chemistry—it uses it to outcompete less-adapted plants.

Honeysweet on the other hand, takes a more flexible approach. Its low profile allows it to capture rare wash runoff and trap sediments both essential survival tools in a landscape dominated by flash floods.

But its superpower is the ability to adjust its photosynthesis to endure extreme temperatures that would halt production in most other species. Controlled laboratory experiments demonstrate that within 24 hours of exposure to extreme temperature(<116F), thousands of genes switch on functions to protect proteins, membranes and photosynthesis machinery from heat damage. It doesn’t just thrive under scorching temperatures, it thrives and grows the hotter it gets.

Together, these two species reveal a simple truth: plants don’t survive despite the heat, salt, and drought—they survive because they have adapted to them.

Why the Earth’s Crust Crumbles in These Hills

The Mecca Hills owe their unusual topography to a small but important kink in the San Andreas Fault. Instead of running straight, the fault bends slightly to the left as its two sides slide past each other. This bend causes the blocks on each side to not only slide past each other (shear) but also get pushed together (compression) at the same time. Geologists called this combination of forces transpression and it’s displayed in this graphic.

Transpression occurring over hundreds of thousands to million of years has caused layers that were once deposited as flat sediment beds to be pushed upward into ridges, as weak rocks are squeezed, broken, or dragged along the fault zone. This explains why the Mecca Hills now stand above the surrounding valley, they reside at this bend in the San Andreas Fault System.

Exploring the Mild Crumble Zone

As we venture further into the canyon, the surrounding hills feature distinct horizontal or gently sloping bands of different colors. What you are looking at is most likely a stack of ancient sediment—mud, silt, sand, and clay—that settled in a calm environment long before this desert existed. These layers were originally deposited as flat sheets and still retain much of that original orientation.

Even though Skeleton Canyon sits inside a very active part of the San Andreas Fault System, not every rock layer near the fault ends up twisted or standing on edge. One explanation for why these horizontal beds show little tilting, folding or uplift is because they belong to a younger, less-deformed sediment layer that accumulated after much of the major folding and uplift in the Mecca Hills had already taken place (100,000 to 200,000 years ago).

Each band reflects a period when different sediment types were delivered into the calm basin that existed here 3–5 million years ago.

Light gray/white bands = sandy or silty river and delta deposits.

Darker gray/greenish bands = clay-rich muds deposited in quiet water.

Tan or buff layers = sandy alluvial fans or wind-reworked deposits.

Entering the Ultimate Crumble Zone

What makes Skelton Canyon landscape so fascinating is that the geology changes in the blink of an eye; calm horizontal layers in one spot and a short distance away wildly bent rock formations exist.

During most of our hikes, we never seen more than a handful of other people. The large group of hikers in some of these photos are present because we now offer this hike as a guided interpretative hike for Friends of the Desert Mountains. Click on the link for more information about these guided hikes. On a side note, look how large and green the cheesebush are along the trail.

In Skeleton Canyon, the San Andreas Fault does more than quietly slide past. It buckles. It crushes. It squeezes and wrenches the crust upward. Sedimentary beds that were once horizontal are now tilted 45° degrees like the beds visible in the background.

This towering sedimentary bed has been tilted nearly vertical by movements along the fault system.

Some hikers hung a skeleton from an outcropping in the canyon wall. Although we are not into displaying artwork in a wilderness area, the skeleton is a perfect addition and a great photo op.

UPDATE: Sometime during 2025 the skeleton was dislodged from the apparatus. We found it sitting in the wash about 1 mile downstream from its original spot. Maybe we should return it to its proper location?

Here is another example of intense, highly-folded sedimentary rock. The dark central pyramid shape is mostly likely a narrow slice of rocks trapped between two faults and is referred to as a ‘fault-bounded sliver’. Like all sediment, it was originally deposited horizontally then cemented into rock and later rotated upright. The evidence supporting this fault-bounded sliver conclusion include:

The pyramid/sliver has sharp, clean grooves that stop abruptly rather than rocks that are folded with gradual bends.

The pyramid/sliver has sharp, straight, clean boundaries rather than the curved bending pattern seen in the adjacent walls.

The pyramid/sliver is darker, harder, and more blocky than the surrounding rocks which are lighter, smoother and more easily eroded.

This mismatch in rock structure, orientation, and composition indicates separate structural blocks are present here and a fault-bounded sliver is the most likely outcome.

Because fault-bounded slivers are composed of harder rock, harder, they erode slower. Flash floods remove the softer rock surfaces, leaving behind the resistant pyramid-shaped fault bound sliver. It’s not unusual for these slivers to present as isolated knives or pyramid shaped.

On several trips, Dave and I explored random openings in the canyon sidewall in search of new routes. We weren't very successful; in most cases the openings closed up quickly.

Chris joined us on one of such adventure. Although, we weren't successful finding a new route, it was still a fun time.

Finding a Slot in the Crumble Zone

They say, 'third time's a charm' and it’s true. During our third trip, we decided to explore an opening that appeared larger than most and it was an excellent choose.

Within a short distance the canyon deepened and the walls started to rise.

We had stumbled into a slot canyon with imposing walls and unlike our previous attempt this slot didn't come to a quick end.

At first glance, Skeleton Canyon seems like the last place you’d expect to find a tall slot canyon. The rocks here are broken, weak, fault-chewed rock, shouldn’t everything just collapse into wide, sloppy gullies? The answer lies in the patchwork of rock strengths found in the canyon.

Fault gouge and mudstone are among the weaker rock formations in the canyon. They offer little residence to the fast and violent flood waters. So erosion happens quickly, forming deep but also wide openings like in this section of the canyon.

Cemented conglomerates and compacted sandstone are tougher formations. When floodwaters encounter these resistant rock layers, they vigorously erode downward, forming a narrow opening with minimal or no material removed from the sidewalls. When these rock formations in the walls erode, they split in clean vertical slices that keep the canyon narrow rather than collapse in piles.

In some areas, the slot is wider and it feels like you’re walking in a vertical rock corridor. Though canyon widths vary the towering walls remain a constant.

If you pause while walking through the slot canyon, you'll see the changing shapes of the canyon aren't random. They reflect the natural patchwork of strong and weak rocks within the fault zone. Once you know what to look for, each layer reveals why one part of the slot holds its shape while another slumps into a sand pile. It doesn't take a geology background to see these patterns.

Every bend tells the story of fast moving water chasing lines of weakness in the canyon walls. In this spot, the walls look smooth from a distance, up close you can see two very different behaviors in the rock. On the left, the wall is made of crumbly, slope-forming mudstone that breaks down into rounded ledges and piles of loose chips at your feet. On the right, the wall looks smoother and more sculpted. That’s because it’s made of slightly better-cemented sandstone and siltstone, which can hold a vertical face long enough for flash floods to carve it into curves and flutes.

In this section, you get a close-up look at how different rock layers respond to the same forces in totally different ways. The wall on the right is made of tougher, better-cemented sandstone and siltstone. Even though the rock is fractured from movement along the faults, its hardness allows it to erode into smooth sweeping curves rather than collapsing. On the left, the wall looks rougher and more crumbly. That’s because it’s made of weaker mud-rich sediment that breaks down easily when it gets wet. Flash floods pluck chunks from this side, widening the canyon here while the stronger wall across from it stays steep and intact. It’s a tug-of-war between rock strength and the power of rushing water.

The graceful curves in the slot-canyon walls come from the way well-cemented sandstones, pebble-rich conglomerates, and tightly packed siltstones respond to fast, sand-laden flash floods. Even though the walls have been fractured by fault movement, the grains inside are locked together by mineral cements. When a flood surges through a narrow passage, water speeds up and begins to spiral. This creates helical flow, a corkscrew-shaped current that scrubs the canyon walls instead of cutting straight down the middle. Over time, those corkscrew flows shave these walls into smooth, curving surfaces.

There is more to see than weak and strong rock layers and curved canyon walls. Up ahead on the wall is a large vertical crack. These straight fractures are signatures of the San Andreas Fault System; evidence of rocks being stretched, squeezed, and shifted as blocks grind past one another. It's a reminder that without the fault zone beneath our feet, these dramatic passages and canyons wouldn’t exist

There isn’t a single end point in this segment of the canyon. It continues but after a long stretch the canyon begins to open, the walls begin to shrink and debris clogs the path.

Our decision to turnaround is usually based on a combination of factors including water supply, temperatures and when we’re satisfied with the day’s effort.

One last photo before we return to the main wash.

On the way back, we paused to get a closer look at this full flowering brittlebush. Don’t be fooled by its appearance, when the heat intensifies, brittlebush knows how to play it safe. Leaves may turn yellow, crisp, or even fall away altogether. This isn’t sickness; it’s strategy. By shedding its water-hungry foliage, the plant protects itself until the rains return.

The tight passageways have given way to the open gravel flats and clear views of the surrounding hills. Walking out of Skeleton Canyon, it's clear that this landscape isn't random or chaotic. It's organized by fault movement, filtered by rock strength and refreshed by flash floods.

This trail has turned into one of my favorites in the Mecca Hills. It's our preferred choice when family and friends come to visit. It has also become a favorite for Friends of the Desert Mountains guided interpretive hiking program.

07112025

Comments