Solitude and Schist: Plenty of Both Hiking in Orocopia Mountain Wilderness

- Steve

- May 4, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Nov 26, 2025

The 18-mile long Orocopia Mountains are a seldom visited range south of Joshua Tree National Park, east of the Chocolate Mountains and west of the Mecca Hills. With the Chocolate Mountains classified as a military restricted area and outstanding hiking to be had in Joshua Tree and Mecca, the Orocopia Mountains only see a handful of hikers each year.

Established by the California Desert Protection Act of 1994, the Orocopia Mountain Wilderness Area (OMW) is situated within the Orocopia Mountains. This Wilderness Area safeguards the central and eastern parts of the range with its wild and geologically fascinating landscapes: vibrant eroded canyons, steep ridges, and deep washes. However, the OMW area includes only a portion of the mountain range.

Hike Distance: 6.3 miles

Elevation Gain: 389 feet

TrailsNH Hiking Difficulty Calculator: 70 – Moderate

Click here to navigate to the TrailsNH website for a description of the hiking difficulty calculator

Let's Go Hiking

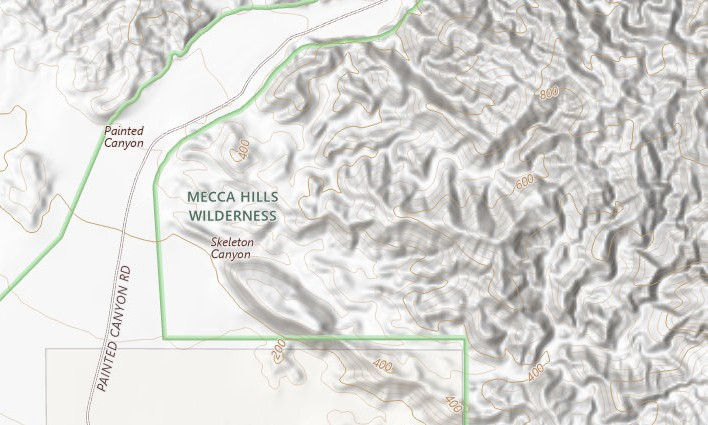

Since this was our first time hiking in the Orocopia Mountains, we opted to start with an easy trek along Red Canyon Trail. The trail is a ribbon of a road that runs through the heart of these mountain and includes a 6.5 mile stretch through the OMW. While vehicles are generally prohibited in wilderness areas, the Bureau of Land Management allows motorized vehicles to use this 6.5-mile stretch but limits their access to a narrow 60-foot wide corridor. Beyond the corridor, motorized travel is not allowed. This map illustrates the Trail’s path through the green-shaded area.

Most hikers arrive at the Orocopia Mountains from one of three routes: north via I-10 near Chiriaco Summit; west via Box Canyon Road; or south via the Bradshaw Trail. For today's we chose the route through Chiriaco Summit. After leaving the highway, we took Summit Rd to Pinto Rd. We continued on Pinto Rd for 1.5 miles until we spotted a kiosk on the left side of the road, which indicated the entrance to Red Canyon Trail. Below is a portion of the map shown on the kiosk.

We traveled approximately 2 miles along Red Canyon Trail before we parked the car due to the worsening soft sand and general road conditions. A word of caution: our 2-mile journey was based on my personal comfort level driving on this primitive road so consider this distance as a guide and not a recommendation. These road conditions can deteriorate quickly; a manageable drive on a Monday may be inaccessible by Wednesday. Your decision on how far to drive should be based on your own comfort level and the road conditions you encounter.

During our hike to ‘remote’ areas, I’ve gotten in the habit of dropping a GPS pin on Google maps to help locate the car if we get disoriented or turned around. Following this practice makes a world of sense.

An Abundance of Solitude

These were the views as we started hiking; solitude and a wide-open expanse with nothing in sight accept more desert.

When hiking in the Orocopia Wilderness Area, I suggest setting specific goals, such as the distance or duration of your hike and the direction you plan to travel. Of course the first step is to check local weather conditions, this is no place to get caught in a rainstorm. We aimed for a 5-6 mile hike that generally followed the road, but we did explore off-trail whenever something interesting caught our attention.

Without discouraging you from exploring these mountains, it's important not to underestimate how disorienting this wilderness can be. Here are some reasons why it's easy to get lost here:

It’s a Labyrinth: The Orocopias are carved by countless dry washes, slot canyons, and branching gullies. These channels often look similar, and once you drop into one, they can wind and split unexpectedly. It’s easy to take the wrong fork and end up miles from where you thought you were heading.

Few Trails & No Signs: Unlike national parks and monuments, the OMW is minimally developed — no maintained trails, no signs, and no water sources. Navigation is entirely up to you.

Repetitive Terrain: The mountains are full of beige, brown, and tan ridges, with little vegetation or tall landmarks. Without a distinctive peak, everything starts to look the same.

Remoteness: The wilderness is bordered by I-10, but once you hike in, you quickly leave roads behind. The area feels surprisingly isolated — if you get turned around, there’s no guarantee you’ll bump into another hiker.

At the end of the post, I’ll provide a few pointers for ‘staying found’ rather than ‘getting found’.

It's time to begin exploring.

Read the Landscape Like a Geologist

This tortured desert landscape resulted from a complex history of fault movement that dates back over 40 million years. The timeline looks something like this:

80-40 million years: Compression along fault lines resulted in marine sedimentary rocks being buried 12-18 miles beneath the crust of the North American Plate. The heat and pressure at this depth metamorphosed the marine sediments to Orocopia Schist.

30-20 million years: Tectonic settings changed from compression to extension, leading to a period of crust thinning which contributed to the deeply buried schist being uplifted and surface erosion exposing the schist at the surface. This schist comprises the core of the Orocopia Mountains.

20-15 million years: During a second period of extension, a crustal block bordering the Orocopia Mountain fault dropped down. This area is known as the Diligencia Basin which acts as a sediment trap.

5 million years to present: Complex movement along the San Andreas Fault Network created further uplift. In some areas, crustal block were squeezed upwards and twisted sideways while other areas experienced downward vertical movement known as subsidence.

To highlight how precariously positioned this region is among these intense tectonic forces, I entered the latitude and longitude for the hike starting point on the interactive fault activity map of California. It pinpointed our position (circled blue marker) as sandwiched between a handful of faults including Chiriaco, Orocopia Thrust, Hidden Springs, Salton Creek, and San Andreas Faults. It's no wonder this is such a deformed tortured landscape.

As we hike, the impact of these tectonic forces is clearly visible. It’s a matter of reading the landscape and applying basic geology concepts. Looking north on the Red Canyon Trail, the landscape is marked by short, steep ridges that abruptly emerge from the desert floor. In this region, the Orocopia crustal block was uplifted and tilted along one of the many faults. Resistant rocks including slices of schist and other basement rock were shoved upward, producing the sharp ridges we see today. Erosion then stripped softer rocks away, leaving the steep profile of the erosion-resistant schist.

Movement along these faults involves not only uplift creating mountains and ridges but also subsidence creating the Diligence Basin. After climbing a hill, I captured this photo looking west across the basin. This sinking block acts as a catch basin for materials eroded from the surrounding ridges and mountains. It's estimated that the basin is filled with a 1-mile thick layer of sediment.

Finding Plants that Survive on Almost Nothing

This hike isn't solely focused on geology; there is also fascinating plant life flourishing in this area. Beginning at an elevation of 1,800 feet, we traverse a desert transition zone where the plant communities of the low and high deserts converge. We can expect to see a unique concentration of plant from both ecosystems. This flowering blue palo verde, which thrives at various elevations ranging from sea level to 3,600 feet, serves as a prime example of such a plant. Unlike most trees, palo verdes can shed their leaves during drought and still perform photosynthesis through their distinctive green bark and branches. This adaptation allows them to survive during the hottest and driest months. Additionally, they possess intricate and efficient root systems. Their taproots can grow deep to quickly to reach groundwater, while their extensive lateral root system enables them to benefit from short rainfalls.

Scattered along the trail were several cacti, including this fragile-looking branched pencil cholla. This species is aptly named for its pencil-width branches that look like they would break with the slightest pressure. However, those thin branches are its advantage. By keeping stems slender and green, pencil chollas maximize photosynthesis while reducing water demand. Thin segments heat up quickly, allowing rapid energy capture in the cool mornings before the desert sun becomes punishing. In addition their open and extensive branching casts shade over their own roots, reducing soil temperature and evaporation.

Due to the limited water storage capacity of its narrow stems, the branched pencil cholla has developed adaptations. It employs a shallow root system to collect water from short rainfalls and a deep root system, which can extend up to 5 feet, to compensate for the narrow stems by gathering sufficient water.

This 15-foot tall ocotillo seems to also enjoy conditions in the Diligencia Basin. Ocotillo prefer a habitat that is open and rocky where soil drains quickly to prevent root rot; all conditions found in the basin. They also prefer an environment with ‘pulse rain events’ characterized by intense, localized storms following long dry periods. Sparse rainfall from winter storm and and important summer monsoons provide just the right blend of dry and wet conditions. They are very picky about the timing of rainfall. According to research conducted by the University of California Riverside, the presence of ocotillo colonies ties directly to regions were summer rain is most dependable. All these 'preferred' conditions are found in the slopes and basin of the Orocopia Mountains.

We observed these ocotillo blooms in early May. Each cane or stem culminates in a dense, cone-shaped cluster that can reach up to 10 inches in length, featuring dozens of bright orange-red to crimson slender tubular flowers. These flowers are ideally shaped for hummingbirds to pollinate and extract nectar from.

While their main blooming period is from March to May, ocotillos do not adhere to a strict schedule, instead reacting to rain and warm temperatures. Due to climate change and increasing temperatures, there is proof that ocotillos are flowering earlier. In 2007, Ecologist Janice Bowers analyzed data and discovered that ocotillos in the Sonoran Desert were blooming 40 days sooner than they did a century ago. A more recent study in 2021 found the ocotillo are now blooming about two weeks earlier that they were just a decade ago. Although this change might seem minor, it significantly impacts hummingbirds, which rely on the nectar-rich ocotillo blooms for energy during their winter/spring migration. With earlier blooming, late-migrating hummingbird species may arrive to find the flowers have already bloomed and gone to seed. This lack of food could have disastrous effects on hummingbird populations, as few other plants provide a consistent source of nectar during their migration period.

Today's hike featured several 'firsts': it was the first time hiking in Orocopia territory and the first encounter with a cottontop cactus. This cactus creates dense clusters or mounds of barrel-shaped heads, occasionally exceeding 100 heads, though 20 to 40 is more typical.

The plant derives its common name from the woolly hairs that appear on the cactus during its seasonal cycle. In summer, the cactus produces bright yellow flowers. After the flowers dry up, a fruit forms. This fruit is a dry shell that develops a crown of woolly hair on the cactus crown and around the seed pods. The transition to seed is finalized when birds and small mammals break open the dry, ripe fruit, using the woolly crown for their nests. This disturbance prompts the release of seeds, ensuring the continuation of the next generation.

Watching the Weather

By the time we stopped for lunch, heavy cloud-cover blanketed the area. Despite the forecast calling for cloudy conditions but no rain, we continued keeping an eye on the sky for the remainder of the hike.

We climbed a series of hills to find a good lunch spot that gave us a birds eye view of the

Wilderness Area.

I climbed higher while Dave (red circle) was eating lunch.

Heading to the Gold Hills

After lunch, we continued hiking for an additional hour. Right when we were about to head back, we spotted a gold-colored ridge in the distance. Since it was still early in the afternoon, we decided to take a closer look.

As a geology enthusiast, I hoped the outcrop would be Orocopia Schist. This schist is a layer of rocks born at the bottom of the ocean more than 70 million years ago. Back then, sand, mud, and bits of volcanic ash were scraped off the seafloor and dragged deep underground by a subducting tectonic plate. Under tremendous pressure and heat, those soft sediments were 'cooked' into metamorphic rock. Later, when the crust was stretched and faulted, the schist was hoisted back up to the surface. As I stood on this outcrop, I was certain it wasn't Orocopia Schist. It lacked the foliation and shiny look characteristic of typical schists, but I wasn't sure of its identity.

After the hike I began researching answers to this mysterious rock. The best answer I found is that this outcrop is 'diagenetically altered Diligencia Basin sandstone'. These sandstones were not created by ancient seafloor subduction. Instead they formed over 15-30 million years ago when thousands of meters of sediments from erosion of nearby mountains and higher terrain settled in the basin.

The shallow depth at which these sediments were buried (<1.5 miles deep) initiated diagenetic processes by which sediments are transformed into sedimentary rock. Successive layers of sediments deposited in the basin were compacted and then cemented by minerals precipitating from groundwater and diagenetic fluids circulating within them. For the rocks shown below, the purple-red mottling is caused by fluids with iron oxides seeping through cracks and staining the rock over millions of years. Fluids with hematite produce deep red and purple colors, whereas fluids with goethite impart a yellow-brown to rust hue to the sandstone.

Unfortunately, it was only after the hike that I discovered the belt of Orocopia Schist does not reach into the Diligencia Basin. With hopes dashed of seeing Orocopia Schist, I now have an excuse to hike in the Orocopia Mountains on another visit. Here's a comparison photo highlighting the similarities and differences between these two rock specimens.

In addition to the diagenetically altered sandstone of the Diligencia Basin, the area was littered with baseball-sized pieces of quartz. These fragments primarily originate from weathered quartz veins in the basement rocks north of the basin. They are more resistant to weathering and erosion, allowing them to persist even when the surrounding sandstone or schist matrix erodes away.

After 2 hours in the wilderness, it was time to turn around and make our way back to the car.

Today's introductory hike in the Orocopia Wilderness Area was fantastic and is the incentive I need to return in the future and attempt a hike in the Orocopia Mountains. While some deserts overwhelm you with their vastness, the Orocopias achieve this through instant seclusion.

Staying Found vs Getting Found

The following points apply to any hike not just hikes in remote areas. You may not get lost but a twisted ankle or other injury can create navigation challenges similar to getting lost.

The Orocopia Wilderness is one of those places where 'getting turned around' can happen fast — even to experienced hikers. Here are some strategies to keep your bearings and make your adventure safe. This information is also relevant for dealing with an injury that prevents you from returning to your car or trailhead. After reviewing this information, you may want to consider adjusting your hiking gear to include some of these additional supplies:

Staying Found: Active navigation and awareness of surroundings

Plan Ahead

Wear a bright-colored shirt, top or jacket. The most visible colors from the air are typically fluorescent orange, blue, green and red, all of which can be seen for several kilometers from the air. Don't blend in with the desert terrain.

Study trail maps and descriptions. Know key landmarks. Download a map and carry a paper map. Bring more than enough water.

Tell someone where you are going and your expected return time.

Carry a battery backup for your phone, compass or a compass app. Consider investing in a satellite communication device.

Leave a note in the car with the trail name or destination and your expected return time. Don't worry about someone breaking into your car if they know this information; they'll break in anyway if that was their intention.

Navigate Actively

Check map/GPS often not just when you're uncertain.

Track your time and distance often.

Be aware of your surroundings and pay attention to the trail.

Use Ridges, Not Washes, for Orientation

Washes twist and split like a spiderweb, and they often look identical. Instead, climb up to a low ridgeline when possible. From above, you can see the direction of the main valleys and use distant landmarks like the Salton Sea (to the south) or Interstate 10 (to the north) to orient yourself.

Learn the Mountain’s Compass Points

The Orocopia Mts run roughly east–west.

Knowing that simple fact helps you recognize whether you’re drifting north toward the freeway or south toward the desert basin.

Take Note of Geologic Features

The rocks here can actually help you navigate:

Bright white quartz veins stand out and can mark specific outcrops.

Darker schist ridges often form the backbone of the higher peaks.

Rust-red canyon walls can anchor your memory of a wash.

Snap a quick photo with your phone of distinctive rock formations to use as 'breadcrumbs' on your return.

Use the Sun as Your Guide

In the desert, shadows are sharp.

Morning sun = east; afternoon sun = west.

This is especially useful when GPS glitches inside narrow canyons.

Always Carry Redundancy in Navigation

Bring a paper topo map and compass — GPS and phone apps are great, but batteries die fast in desert heat.

Download offline maps before your trip; cell service drops once you leave I-10.

Mark Your Entry Point

Many people get lost simply by not recognizing where they entered a canyon.

Drop a GPS pin, tie a small marker ribbon (pack it out later), or note a unique feature like a boulder pile or palo verde tree at your entry.

Pace Yourself and Take Breaks

Dehydration and heat exhaustion reduce awareness.

Drink regularly, stop in the shade when possible, and mentally check in with your direction every half hour.

Know Your Bail-Out Points

North = I-10 freeway; about 3–5 miles away from most points.

South = the wide open Salton Basin; but it's far more remote, with little chance of rescue.

If you're unsure, head north and make your way to the interstate.

Getting Found: Make yourself easier to locate

STOP Method: Stop, Think, Observe & Plan

Don't keep wandering - it spreads confusion.

Stay Put

Once you recognize you're lost, settle in a safe location near open space or your last know trail or landmark.

Signal for Help

Use bright clothing or emergency blanket laid out in the open.

Whistle blast: three short blasts is the signal for distress.

Use a flashlight at night.

Use rocks to make an SOS or arrow or even a large X.

Make Yourself Visible

Move to a clearing or ridge top where searchers can see you from the air.

Use your Tech

Activate satellite communication device.

If there no cell signal, consider turning off your phone periodically or using low battery and airplane mode to prolong battery life.

Conserve Energy

Focus on staying warm, hydrated and sheltered.

Stay positive and don't panic.

Stay safe and keep hiking!

040523

I appreciate the thorough summary. The investigation of interactive digital services illuminates their increasing influence on entertainment. There is more material on the website for those who want to read more. The post does a good job of capturing the subtleties of this topic.